What Gets Measured Gets Manipulated

How metrics mislead, incentives backfire, and what to do instead.

Before we dive in, Screenwich is a tool I built with a few friends to make stock analysis a little less painful.

It helps you screen for promising stocks, analyze price trends, and even calculate fair value, all in one place. And yes, it’s free.

Check it out👇🏽

Robert McNamara won at Ford by trusting numbers. Then he tried to win a war the same way.

In October 1966, Robert McNamara, the U.S. Secretary of Defense, stood in a sweltering tent. His days at Ford had taught him that numbers brought clarity, control, and progress1. So he brought spreadsheets to the battlefield in Vietnam.

Each morning, his aides delivered updates: "Enemy casualties rising. Territory captured increasing. Bomb tonnage doubled".

But on this day, a Marine colonel offered something different, a briefing on guerrilla warfare, focused on context and people.

McNamara interrupted, “Now, let me see if I have it right, this is your situation", and then he spouted his own version, all in numbers and statistics. The colonel had to agree2.

But it was far from the reality.

Jack Raymond, a journalist from The New York Times, laughed at the absurdity. But McNamara didn’t flinch.

Later, McNamara praised the colonel as “One of the finest officers I’ve ever met”.

The numbers kept climbing. But progress never came.

Because body counts and bombing runs couldn’t capture morale, motivation, or meaning. The metrics said one thing. The reality said something else.

That moment became symbolic of a broader problem: when we rely only on numbers and ignore the harder-to-measure factors, we lose sight of the full truth.

This mistake is known as the McNamara fallacy.

Never ask the village barber if you need a haircut.

— Warren Buffett, The University of Berkshire Hathaway

This Isn’t Just History. It Happens at Work.

Wells Fargo set a goal: eight accounts per customer3. Bonuses were tied to it. Employees created millions of fake accounts to hit the number. The metric looked great, until trust collapsed.

At Amazon warehouses, productivity is tracked by packages per hour. Bathroom breaks dropped, injuries went unreported, workers collapsed. The numbers stayed high, but the human cost rose even higher4.

As Morgan Housel puts it in The Psychology of Money:

Incentives are expert storytellers, able to convince you that nonsense is real, harm isn’t happening, value is being created, and that whatever you’re doing is just fine.

We look where the light is brightest, not where the truth lies.

Morale is measured by pulse surveys, not by genuine motivation.

Productivity is measured by hours, not by quality of ideas.

Collaboration is measured by the number of meetings, not by what gets accomplished together.

And the things that matter more, like trust, culture, and integrity, stay hidden in the shadows of metrics.

🚨 Quick sidebar: Enjoying what you are reading? Sign up for my newsletter to get similar actionable insights delivered to your inbox.

Pssttt… you will also get a copy of my ebook, Framework for Thoughts, when you sign up!

When a Metric Becomes the Mission

As explained in Super Thinking, which explores various mental models, British economist Charles Goodhart once warned:

When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.

Metrics start innocently.

🔢 Leaders crave clarity, so they pick something easy to measure.

🎁 Then come the incentives, bonuses, promotions, recognition, all tied to that one number.

🏃 Employees start chasing the metric, not the mission.

🎯 The number gets hit, but the outcome it was meant to represent gets lost.

The metrics that begin as a tool for focus becomes a distraction.

This is why sales teams hit quotas without building trust. Why schools teach to the test. Why innovation slows when people optimize for what’s measured, not what matters.

It’s the McNamara Fallacy in action.

It’s Goodhart’s Law.

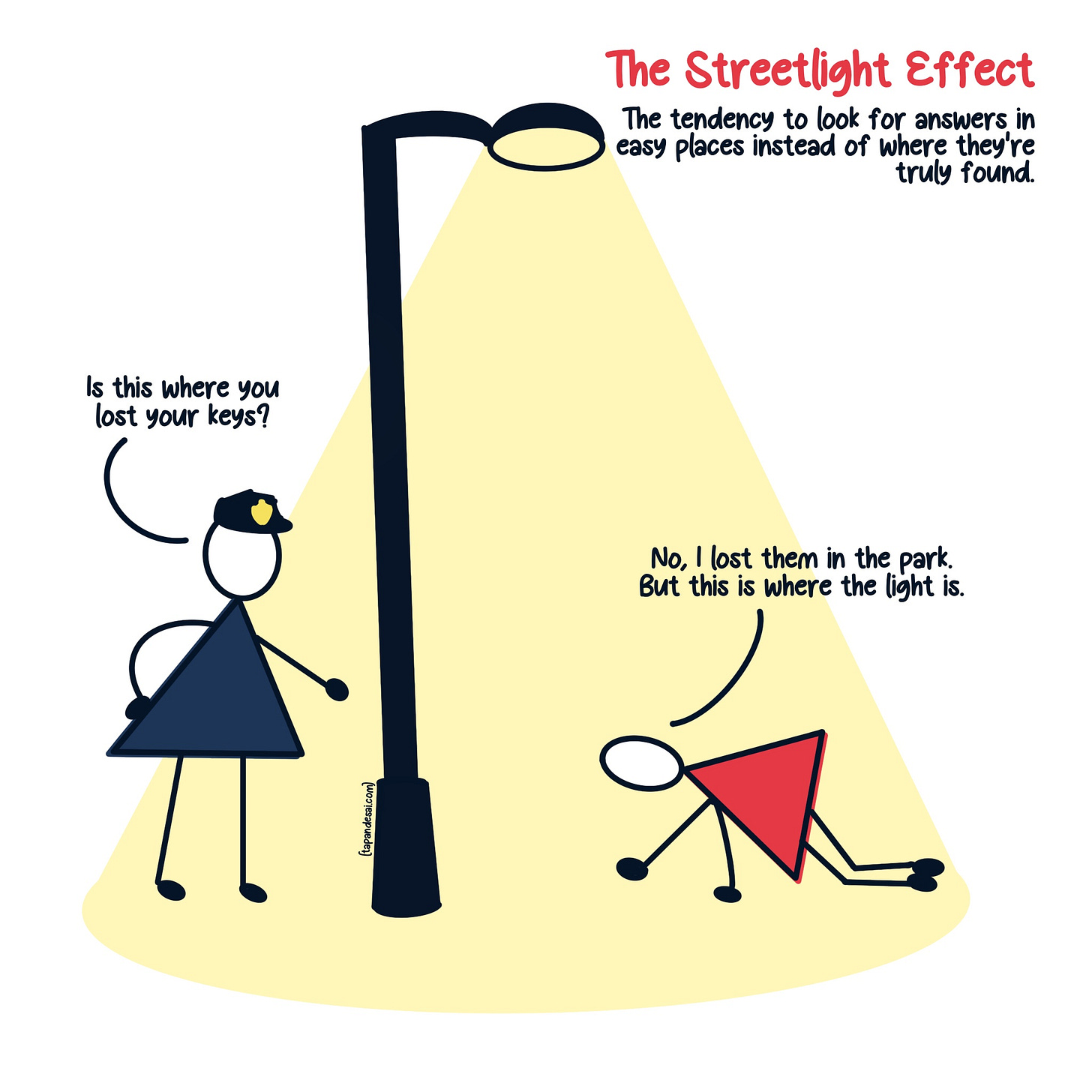

It’s also the Streetlight Effect, looking only where the light (or data) is, not where the answer might be.

And sometimes, it’s worse.

In colonial India, British officials offered bounties for every dead cobra to reduce the snake population. Locals began breeding cobras, killing them for the reward. When the program was shut down, the breeders released the snakes, and the problem got worse.

The lesson? Misaligned incentives don’t just fail, they often backfire.

Designing Incentives That Actually Work

You don’t need to ditch metrics. You just need smarter ones. Here’s how some companies have build better incentives:

🔍 Pair metrics with stories.

Numbers show what’s happening. People explain why.

Google learned this the hard way5. They once tied bonuses to user growth and the numbers got gamed. Now, they combine data with town halls and 1:1s to understand what dashboards miss.

📈 Reward direction, not just destination.

In Delivering Happiness, Tony Hsieh says, Zappos dropped typical call center metrics like average handle time. Instead, agents were trusted to solve problems however they saw fit. Customers got real help, not rehearsed scripts.

🕵️♂️ Ask what the metric misses.

Before you reward a number, ask: What if someone gamed this?

Toyota did.

Rather than chase production quotas, they reward process improvements and quality6.

The result? Better outcomes, fewer shortcuts.

🌱 Measure the invisible.

In No Rules Rules, Reed Hastings says that Netflix doesn’t track hours or vacation. They care about creativity, accountability, and outcomes. Trust replaces timesheets. Responsibility replaces rules.

🧭 Look beyond the dashboard.

Patagonia rewards environmental activism. Cleveland Clinic pays doctors for outcomes, not procedures.

These orgs ask better questions: Does this build trust Would I be proud of this in five years?

What McNamara Got Wrong (So You Don’t Have To)

Decades later, in the documentary The Fog of War, McNamara confessed, "We were wrong. Terribly wrong."7

Numbers had blinded him to the human truth, the resolve of people fighting for freedom. His painful lesson is your chance for clarity.

Metrics guide but must never govern.

Easy measurements rarely capture complex truths.

Align incentives with meaningful outcomes, not narrow metrics.

Always pair quantitative data with deep, qualitative understanding.

Numbers alone won't show you what truly matters; people do.

Until next time,

Tapan (Connect with me by replying to this email)

Thank you for reading! 🙏🏽 Help me reach my goal of 2,300 readers in 2025 by sharing this post with friends, family, and colleagues! ♥️

As an Amazon Associate, tapandesai.susbtack.com earns commission from qualifying purchases.

Starting as manager of planning and financial analysis, McNamara advanced rapidly through a series of top-level management positions. McNamara had Ford adopt computers to construct models to find the most efficient, rational means of production, which led to much rationalization. McNamara's style of "scientific management" with his use of spreadsheets featuring graphs showing trends in the auto industry were regarded as extremely innovative in the 1950s and were much copied by other executives in the following decades. [source]

The Best and the Brightest by David Halberstam

The term “eight is great” - referring to a target of eight Wells Fargo accounts per customer - became a company tagline. [source]

Though it may seem counterintuitive, OKRs should not be directly tied to compensation or bonuses. Here, former Senior Vice President of People Operations at Google, Laszlo Bock, details the value of purpose-driven goals and explains how to motivate a team using more than just money. [source]

Here I am trying to analyze the impact of a feature we built recently and read this article before I started xP

Great read! Put into words concepts I have seen but couldn’t articulate. Thanks