What Makes an Artist Great?

A 300-year-old painting, a locked room, and three timeless lessons on creativity.

If you want to show support, please hit the ❤️ “Like” button at the top or bottom.

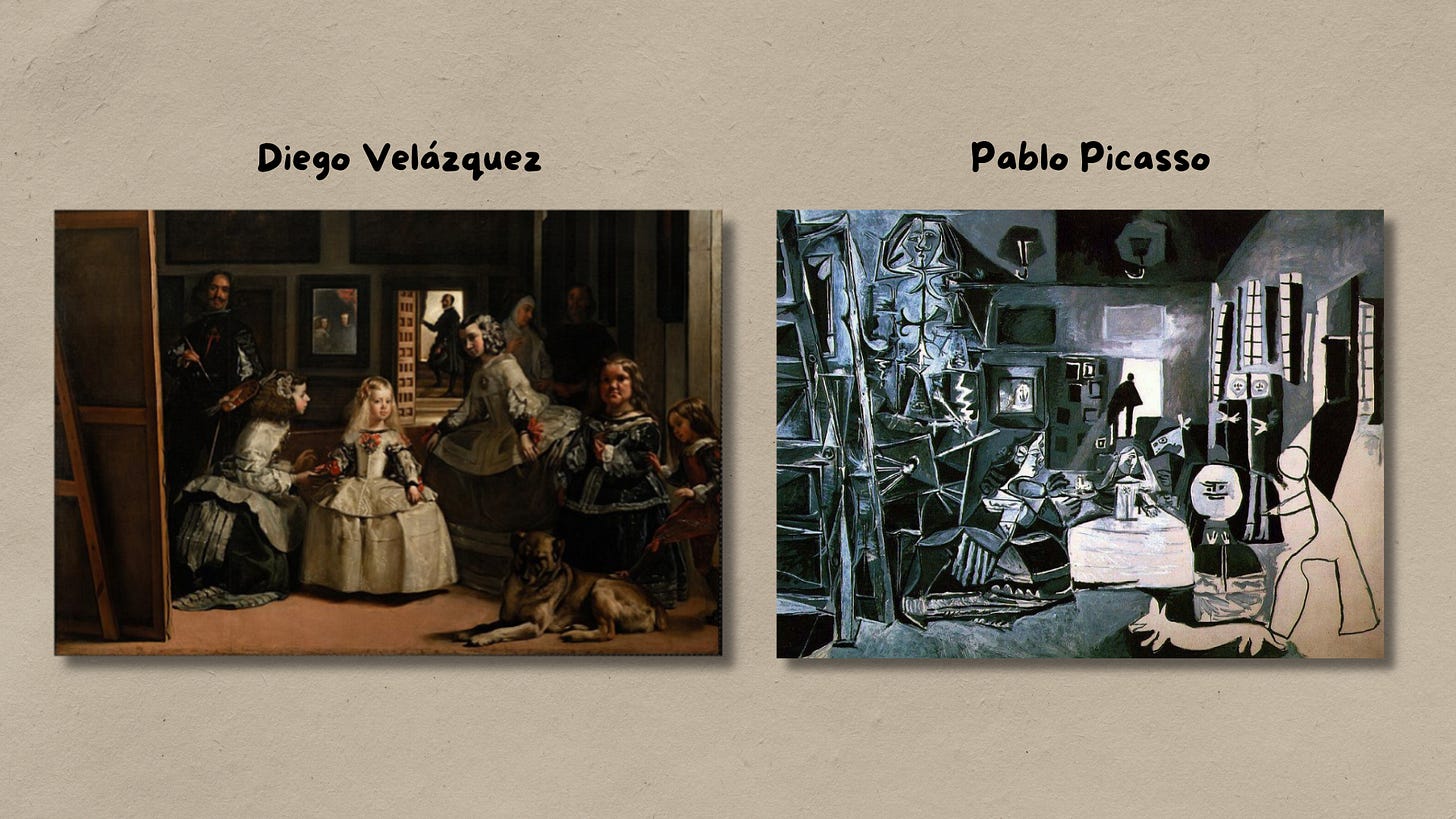

In 1656, Diego Velázquez didn’t just paint a portrait. He painted a puzzle, one we are still trying to solve.

Las Meninas.

At first glance, it’s a royal family portrait. But look closer and the frame starts to slip.

There’s Velázquez, at the far left, painting someone off-canvas, maybe the king and queen, maybe us.

Initially, the painting seems to center on Margaret Theresa, the young girl in the spotlight.

But then you notice the king and queen, barely there, just a reflection in the mirror.

And that’s when it hits you: maybe the real subject isn’t in the painting at all. Maybe it’s you. The viewer. Standing where Velázquez himself stood, caught in the act of observing, as others stare back at you.

It’s less a portrait, more a philosophical trap: who's watching whom?1.

Was it a royal commission? A self-portrait? A philosophical riddle wrapped in oil and canvas?

Yes.

And for 400 years, Las Meninas shaped the greats who came after.

Goya studied it. Manet borrowed its tricks. Dali twisted it. Sargent echoed it2.

But no one went deeper than Pablo Picasso.

In 1957, he locked himself in a studio for four months, not to admire it, but to tear it apart3.

He created 58 versions of Las Meninas4. Not copies. But interpretations.

He didn’t want to replicate Velázquez; he wanted to understand what made the painting breathe.

His obsession wasn’t just an artistic exercise. It was a clue.

A clue to a bigger question: What turns an artist into one of the greats?

Make a Lot of Work (Yes, Even the Bad Stuff)

In Originals, Adam Grant points out that the most successful artists, scientists, and creators didn’t win because they were always better, they just created more.

Shakespeare wrote 37 plays and 154 sonnets. How many do you know? Yes, only a handful became famous.

Picasso made over 50,000 pieces. Fifty-eight were just on Las Meninas. And more than 10,000? Lost, stolen, or simply disappeared5.

Mozart wrote over 600 compositions. Most people only know the ones playing in elevators.

Even Einstein wrote 272 papers6. Four or five changed the world. The rest? Just steps along the path.

Quantity doesn’t compete with quality. Quantity is how you get to quality.

This echoes Malcolm Gladwell’s 10,000-hour rule from Outliers. But it’s not just about hours. It’s the iterations.

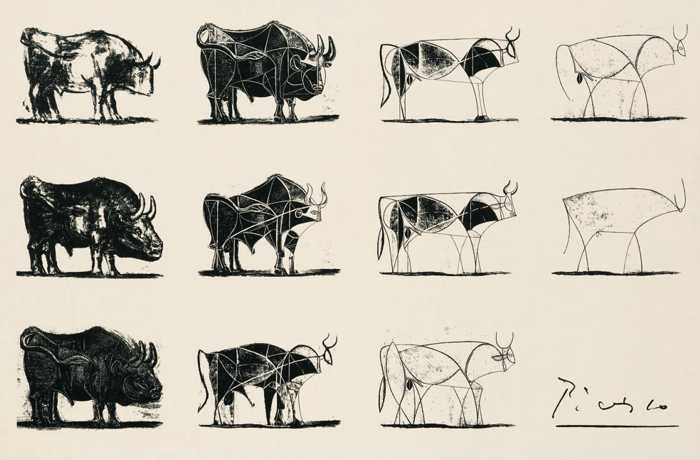

Picasso’s famous Bull series is a perfect example. A single bull, drawn in a dozen ways. Each version simpler, more distilled. By the final drawing, he captured the essence, with just a few lines.

You don’t find your style by thinking. You find it by making.

And not everything you make will be good. That’s not a bug, it’s the system working.

We fail to achieve greatness because we generate a few ideas and then obsess about refining them to perfection.

Even on social media, the most viral creators aren’t necessarily the best. They are just the ones who post enough to get lucky. More posts means more surface area for luck to land.

If you want to do great work, don’t chase perfection. Chase reps.

Perfection is found inside the pile of imperfect things you made along the way.

🚨 Quick sidebar: Enjoying what you are reading? Sign up for my newsletter to get similar actionable insights delivered to your inbox.

Pssttt… you will also get a copy of my ebook, Framework for Thoughts, when you sign up!

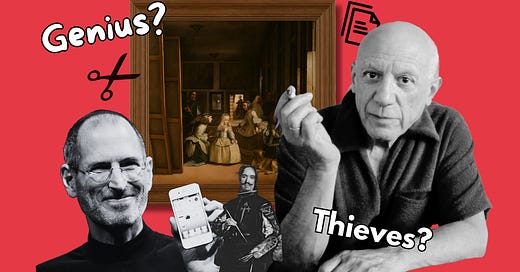

Steal Like an Artist (Then Make It Yours)

When Picasso tackled Las Meninas, he wasn’t copying Velázquez.

He was arguing with him, across three centuries.

He didn’t recreate the painting. He rebuilt it from the bones up. 58 times.

This is how greatness begins: by learning from the greats.

Austin Kleon’s Steal Like An Artist is good starting point.

Copying skips understanding. Imitation seeks it.

Every artist starts with a borrowed voice, a remix of their influences, stitched together with hope.

Steve Jobs borrowed from Sony, Xerox, and even his college calligraphy class. Howard Schultz modeled Starbucks after Italian cafes. Canva reverse-engineered Adobe and made it accessible.

Imitation, when done right, is about understanding the DNA of what you admire.

William Zinsser wrote in On Writing Well,

If anyone asked me how I learned to write, I’d say I learned by reading the men and women who were doing the kind of writing I wanted to do and trying to figure out how they did it.

You can’t help but absorb the styles, rhythms, and tools of those who came before you.

But here’s the truth: You can never fully imitate your heroes.

And that’s a good thing.

You are not them.

You will stumble where they soared. You will make different choices, take different paths. That gap between their genius and your attempt? That’s where you find your own voice.

Imitation isn’t a shortcut. It’s a rite of passage. A time-tested tradition.

We study the greats. We steal like artists. And somewhere along the way, we become ourselves.

Show Up, Every Day

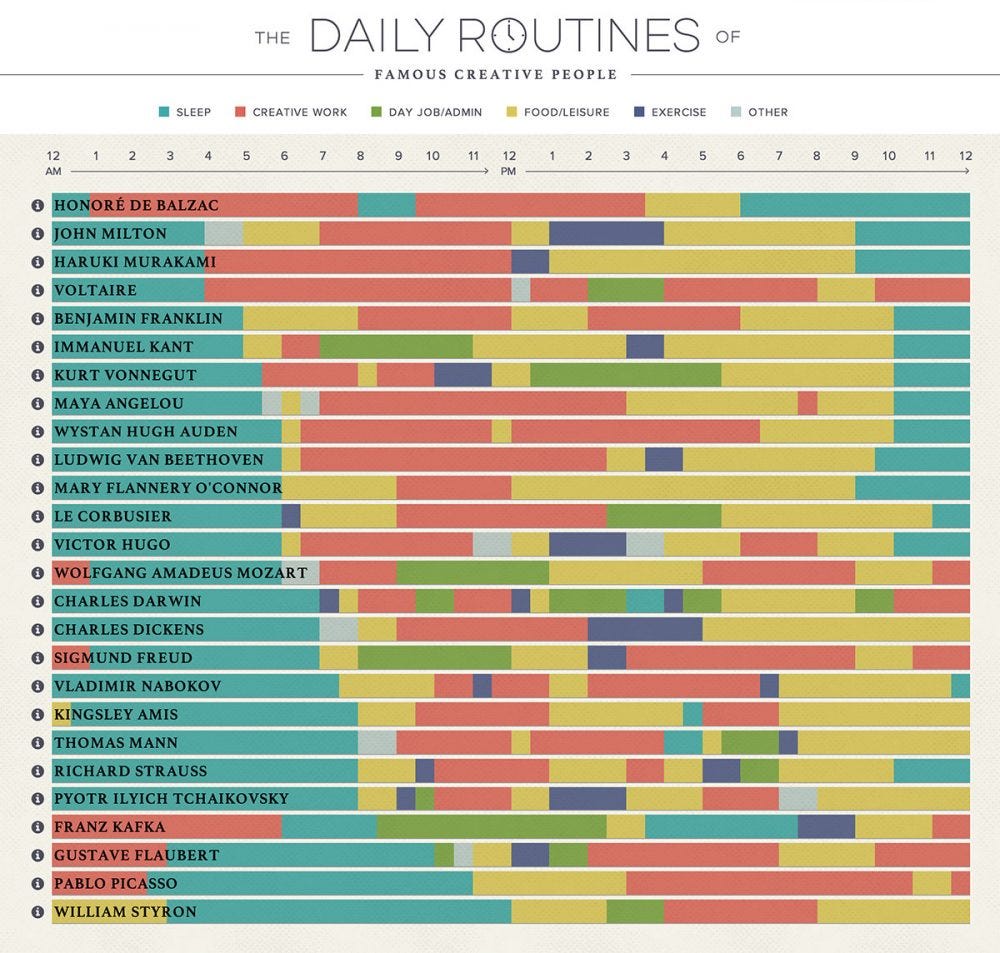

In Daily Rituals, Mason Currey profiles the daily routines of over 150 of history’s most creative minds - writers, painters, composers, scientists.

We picture them as erratic geniuses, struck by lightning bolts of inspiration. But when you zoom in, that myth falls apart.

The truth? They weren’t chasing inspiration. They were building systems to catch it.

And within those systems, they carved out uninterrupted time for deep work. Two to six hours. Every single day. No distractions. No errands. Just full, undivided presence.

Haruki Murakami writes in the mornings and relaxes for the rest of the day.

Mozart composed early, before the noise of lessons and performances.

Picasso blocked entire chunks of his day just to create.

They understood something most people forget: You can't do meaningful work when your mind is already scattered.

Greatness didn’t arrive in a flash. It showed up quietly. Repeatedly. Before anyone felt ready.

Charlie Munger, in Poor Charlie’s Almanack, praised three minds he deeply admired: Newton, Einstein, and Simon Marks, the man behind Marks & Spencer. What struck him most about Marks was simple, “Find out what you’re best at and keep pounding away at it.”

Take one simple thing — almost anything — but take it extremely seriously as if it is the only thing in the world — or maybe the entire world is in it — and by taking it seriously you’ll light up the sky.

- Kevin Kelly, Excellent Advice for Living

That’s the game. Not brilliance. Not multitasking. Just the discipline to do one thing well, and do it over and over until the world notices.

I know what you’re thinking.

“I am not Picasso. I have got meetings, my partner, inboxes, and increasing shareholder value!”

Fair. But this isn’t about becoming a full-time artist.

It’s about finding 30 minutes for the thing that matters. Before the world wakes up. After the kids sleep. Between meetings, if you have to.

Because in the long run, small rituals crush big resolutions. And consistency is the real creative superpower. Not instantly. But inevitably.

As Rick Rubin mentions in the Creative Act,

Surround yourself with great work. Read better books. Study people who built things that lasted.

Eventually, your taste sharpens. You start to see what great looks like.

That’s how mastery is built: Focus. Ritual. Repetition. Not once in a while. Every day.

The Painting Was Never the Point

Las Meninas wasn’t meant to be solved.

It wasn’t painted to impress us.

It was painted to challenge the ones who came next.

That’s what makes an artist great:

They make more than they need to.

They imitate without losing themselves.

And they keep showing up, even when no one’s watching.

Picasso didn’t find greatness in a single stroke. He found it in fifty-eight rewrites of someone else’s idea.

Not to match it. But to meet it.

To sit across from it and ask, “What are you trying to teach me?”

That’s the work. And maybe, if you stay long enough, brush in hand, eyes still learning, it starts to answer back.

Until next time,

Tapan (Connect with me by replying to this email)

Thank you for reading! 🙏🏽 Help me reach my goal of 2,300 readers in 2025 by sharing this post with friends, family, and colleagues! ♥️

As an Amazon Associate, tapandesai.susbtack.com earns commission from qualifying purchases.

This is a beautiful explanation of what makes Las Meninas so great:

Meninas and Infantas: History of a Seduction, 1656-1901 by Javier Portús

His Woman in Blue, of three years later is a paraphrase of Velázquez’s Mariana of Austria and in 1957, on the threshold of old age, he shut himself up for four and a half months with a photograph of Las Meninas, dissecting and reinterpreting it by way of 44 canvases - from Meninas and Infantas: History of a Seduction by Javier Portús

Read a lot of things this weekend. This was the best. Well done!

Your articles are always a treat to read! This was such an interesting take on showing up regularly and working on something that matters.

Good one bhai! :)