Why We Trust Stories, Not Data

From cholera outbreaks to startup myths: how narrative bias shapes our world.

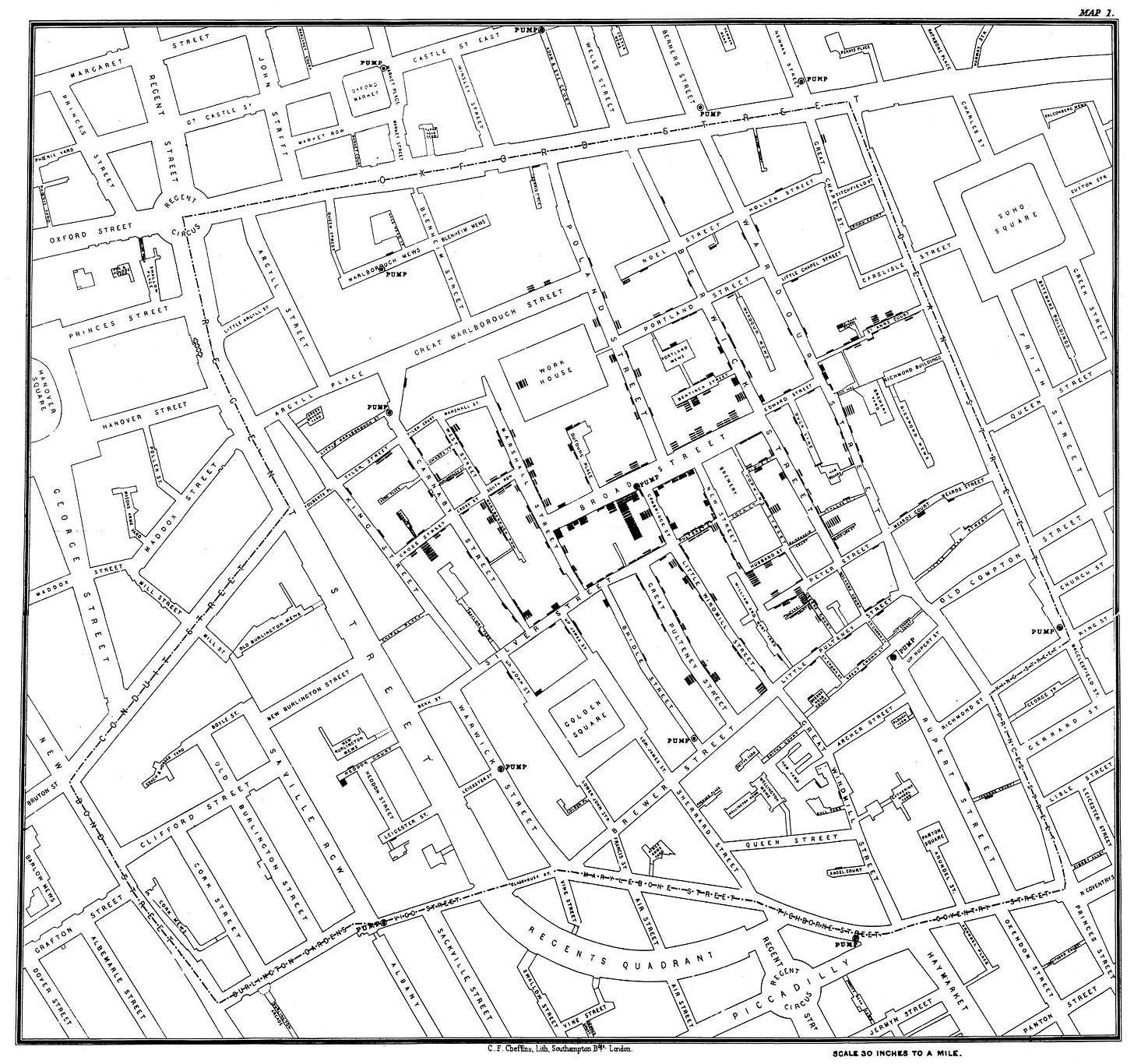

In Soho, there’s an old water pump that changed the course of history, though most people walking by wouldn’t know it.

A few years ago, I stumbled across it while wandering through London. It didn’t look like much, just the kind of thing you’d pass by without thinking twice. In a city like London, these relics are quite common.

But this wasn’t just any pump. This was the Broad Street pump.

In 1854, London was in crisis. Cholera was ripping through the city, claiming thousands of lives in its wake. Desperation hung thick in the air.

Enter Dr. John Snow, a physician who refused to accept the story everyone else believed.

He mapped cholera cases and discovered that the disease wasn’t airborne, it was waterborne.

And at the center of the outbreak was the Broad Street pump.

His findings eventually revolutionised public health, but not immediately1. Why?

Because his truth clashed with the narrative people preferred, they didn’t believe him.

You see, the belief back in the day was that diseases like cholera spread through “bad air” or miasma. It was a theory so deeply embedded in people’s minds that it had held sway since the days of Hippocrates, nearly 2,000 years earlier2.

The logic was simple: cities stank, diseases spread in cities. So, the smell must be the culprit. 😷

It was simple, familiar, and easy to believe for people.

Snow’s evidence, by contrast, was unsettling. It was incomplete. And it asked people to rethink everything they thought they knew. So, they rejected it.

He, eventually, was somehow able to convince the authorities to remove the pump handle, although by that time the worst of epidemic had already passed3.

This love of stories, even flawed ones, isn’t unique to Victorian London. It’s a deeply human tendency–one we call narrative bias.

🚨 Quick sidebar: Enjoying what you're reading? Bet you've got a friend who would too. Share and help me grow this newsletter.

Pssttt… they will also get a free copy of my ebook, Framework for Thoughts, when they sign up!

When Data Gets Lost in the Plot

🚨 Here’s a quick thought experiment:

⛔️ Hope you have locked in your answer.

If you guessed “A”, you’re not alone, but you’re also wrong. While the NYT may seem like a lot of people with Ph.D. would read, there are only about 6.57 million Ph.D. holders in the U.S., compared to over 94 million NYT readers. Statistically, the odds favour “B”.

“Ph.D. holder reading the NYT” fits a tidy story.

Narrative bias is our brain’s preference for stories over data.

It’s why we gravitate toward neat, cause-and-effect explanations, even when reality is messy and random.

Stories feel satisfying.

They’re easier to process, easier to remember, and—crucially—they help us make sense of the world.

Our love for stories over raw data is clear to authors from the sheer number of books on storytelling being sold on Amazon.

Lead with a Story was one of the first books I picked up when I started working, and it completely changed the way I thought about communication in business.

Consider Malcolm Gladwell’s bestsellers like The Tipping Point or Outliers.

They hook us with captivating anecdotes that frame complex ideas.

While the “Malcolm method” is brilliant storytelling4, it sometimes oversimplifies reality or draws conclusions that don’t always hold up under scrutiny.

It works because it leans on narrative bias: we’re primed to believe a good story, even if the data behind it is shaky.

It’s:

🤑 Why investors bet on a company’s story instead of digging into its income statement or balance sheet?

👟 Why Nike makes you believe greatness starts with three words: Just Do It?

😎 Why we love the idea that a college dropout built a tech empire with nothing but grit?

From Survival to Storytelling: How We Got Here

Humans are meaning-making machines.

Our brains are wired to find patterns and construct narratives from fragments of information. This evolutionary quirk helped our ancestors survive by spotting danger and predicting outcomes5.

But in modern life, it backfires. Here’s why:

🧩 Oversimplification: Stories often exclude messy, inconvenient details that don’t fit the narrative.

Take Mark Zuckerberg’s story: a college dropout who built a tech empire. It’s tempting to conclude that dropping out might be the secret to success. Our brains latch onto this success story because they’re easier to process.

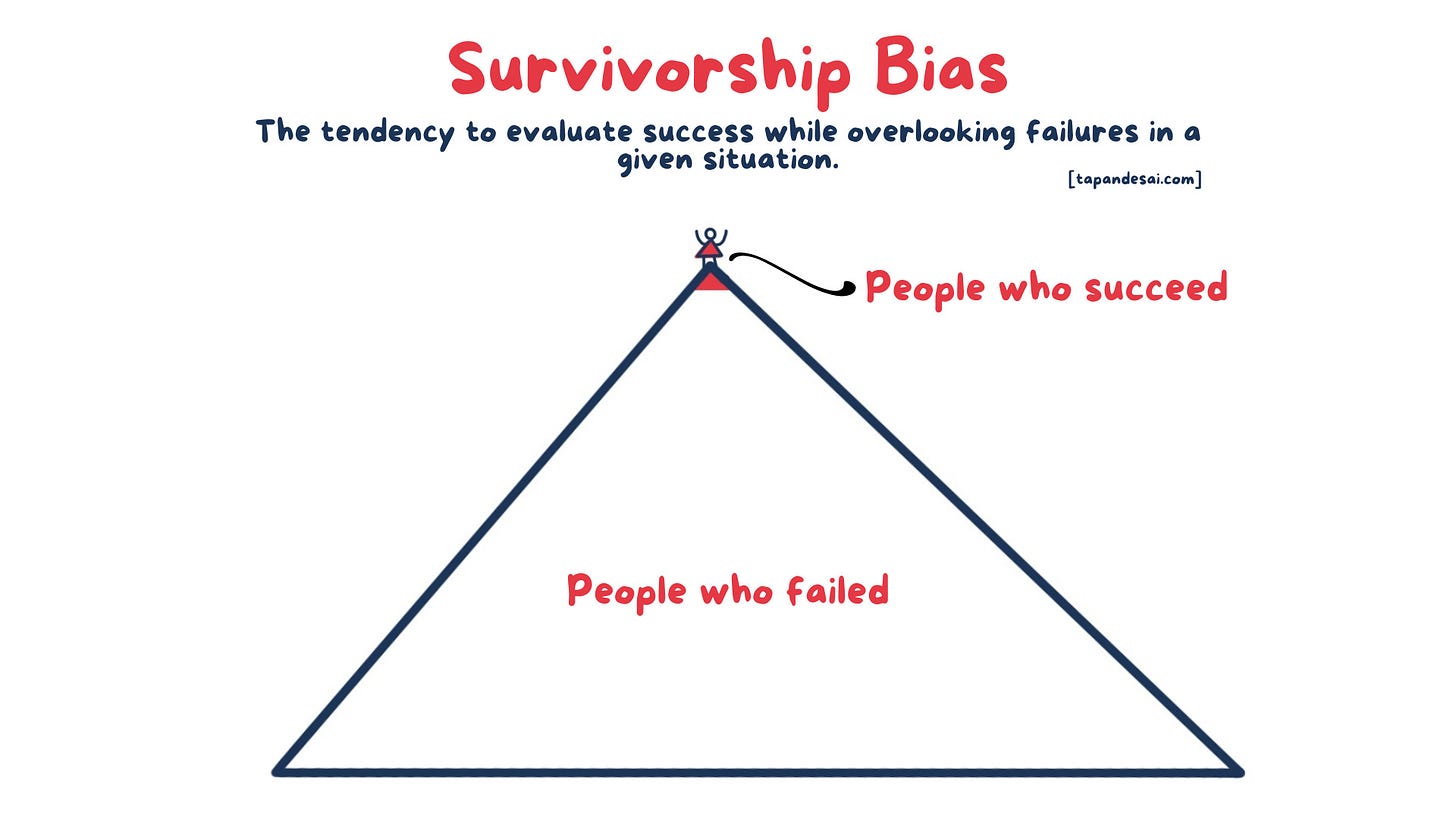

Narrative bias fuels this oversimplification, often working hand-in-hand with survivorship bias. We focus on the visible successes (the survivors) while ignoring the many dropouts who didn’t make it.

It creates a tidy, but incomplete, narrative: “They succeeded because of X”.

🧠 Memory’s Trickery: Memory isn’t a perfect recording; it’s a reconstruction. When recalling events, we fill in gaps to create a logical sequence, even if the actual events were chaotic or random.

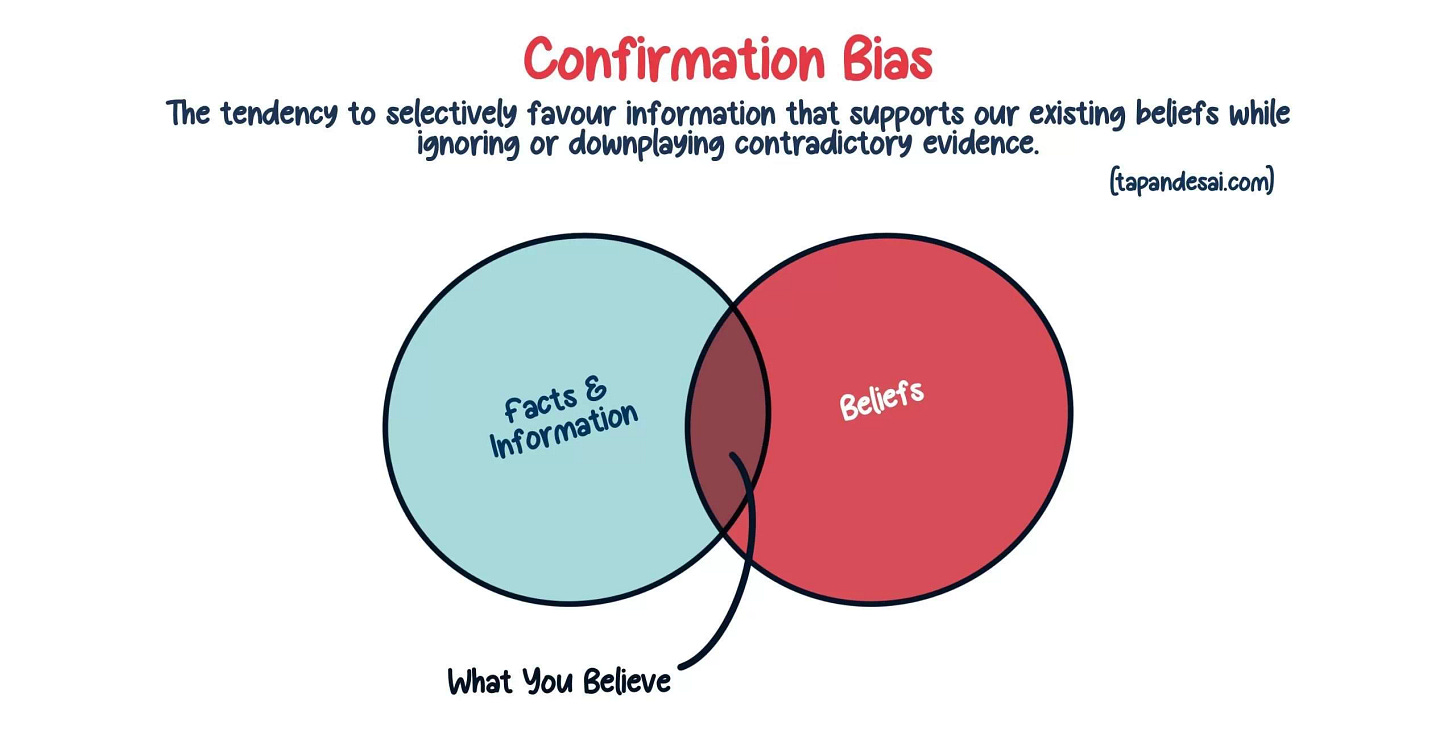

For instance, if you believe a political party is corrupt, you’re likely to remember scandals that confirm your belief while ignoring evidence to the contrary, forming a coherent narrative in your memory.

This overlaps with confirmation bias, reinforcing our faulty narratives.

😌 Comfort Over Complexity: A coherent story feels safe. Randomness, on the other hand, feels unsettling.

We would rather believe in a simple cause-and-effect explanation than accept that luck or chance might be at play.

As Nassim Taleb explains in The Black Swan, randomness is complex and impossible to reduce without losing meaning. In contrast, tidy stories can be compressed into neat summaries, which is why they’re far more comforting—even when they’re inaccurate.

Breaking Free from the Bias Trap

⏸️ Pause Before You Believe: When someone shares a compelling story, ask yourself: does this feel true, or is it actually true? As Charlie Munger reminds us, look for disconfirming evidence.

🕵️♂️ Hunt for Survivorship Bias: If someone claims, “X did Y to succeed,” ask:

“How many others did Y but didn’t succeed?”

“What factors besides Y might explain their success?”

🤔 Ask “What’s Missing?”: Good stories omit details to stay engaging. Dig deeper to find the pieces that were left out.

Life isn’t a clean narrative. It’s a series of overlapping, often contradictory events. The truth might not always be as satisfying as a story, but it’s far more powerful.

Until next time,

Tapan (Connect with me by replying to this email)

Thank you for reading! 🙏🏽 Help me reach my goal of 2,300 readers in 2025 by sharing this post with friends, family, and colleagues! ♥️

As an Amazon Associate, tapandesai.susbtack.com earns commission from qualifying purchases.

John Snow failed to convince many in the medical establishment. (Science Museum)

The ancient Greek physician Galen, working in the 2nd century CE from the medical principles of Hippocrates and others, was the primary proponent of the idea of diseases caused by miasma (pollution) or poor quality air. (Science Direct)

John Snow convince local authorities, a bit too late. (Science Museum)